The First Saddest Day of My Life: A Vietnam Story

History Now: American History Online – The First Saddest Day of My Life

WARTIME MEMOIRS AND LETTERS FROM THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION TO VIETNAM

The First Saddest Day of My Life: A Vietnam War Story

by Sharon D. Raynor

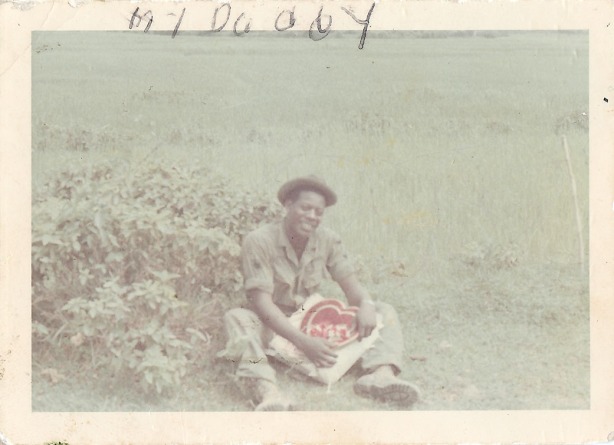

What I know about the Vietnam War, I learned as a child from my father, Louis Raynor. At thirteen years old, I discovered an old, tattered, leather-bound diary in my parents’ chest of drawers. When I opened it, I immediately recognized my father’s handwriting. I was intrigued so I quietly took the small book and ran off to read it. Over the years, from his war diary and photographs, our many conversations and oral history interviews, my father answered my endless questions about Vietnam.

Louis Raynor, 1967

After being drafted and entering the military in 1966 at age eighteen, my father completed basic training at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and then went on to complete advanced infantry training (AIT) at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Aberdeen, Maryland. Basic training during the Vietnam War typically lasted about nine weeks, while AIT usually lasted another eight weeks, and its graduation came with orders to ship to Vietnam. On September 24, 1967, he said goodbye to his family and girlfriend and boarded an airplane from Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, and began his journey to Vietnam. With stops in Chicago, California, and Honolulu, he finally arrived at the Tan Son Nhut Air Base, near Saigon. He was then shipped to the 90th Replacement Company, 9th Infantry Division, the Old Reliable Academy, and later to Headquarter Troops, 3rd Squadron, 5th Cavalry.

The Old Reliable Academy, 9th Infantry Division, South Vietnam, 1967.

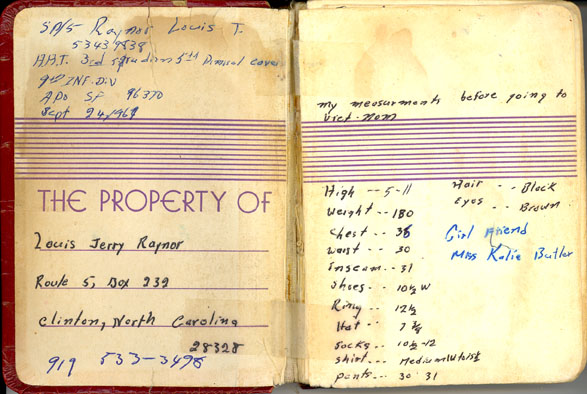

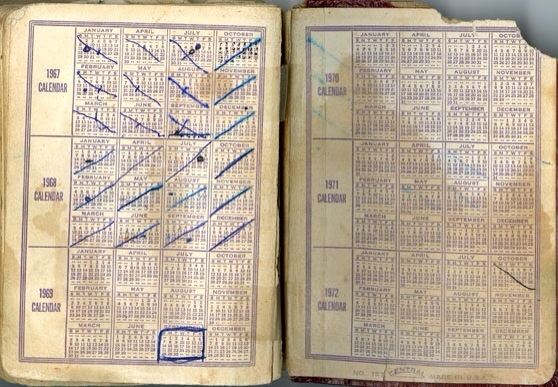

As my father prepared to leave for Vietnam, he started writing in a small, leather-bound burgundy diary measuring 5.5″ x 4″. He served with the 3rd Squad/5th Cavalry, 9th Infantry Division (Black Knights) in the US Army. His Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) was Track and Wheel Recovery. The diary was compact enough for him to keep either in his footlocker or inside his uniform wrapped in plastic to protect it from rain when he was out in the field. Within the front cover of the diary, he wrote all of his essential personal information: name, rank, unit, date of departure for Vietnam, body measurements, home address, and telephone number as well as the name of his girlfriend, who would become his wife and my mother once he returned home. On the first page of the diary (January 1), he scribbled a note to turn to September 24. Since his tour of duty, which during the Vietnam War was typically 365 days, began September 24, 1967, the diary begins in the middle and reads according to the days of his tour from September 24, 1967, to September 23, 1968, covering September to December and then continuing from January to September. Instead of counting the days of his tour in chronological order, from Day 1 to Day 365, my father does a backwards countdown, indicating his first day in Vietnam as Day 365 and to his last day in Vietnam as Day 1. The very first entry in the diary is September 24, 1967, which is the day he was supposed to leave for Vietnam, but because of delays at the airport, he marks September 26, 1967, as Day 365, indicating the day he actually leaves home for a twelve-month tour of duty in Vietnam. As his tour came to an end, he wrote the last few days as multiple entries on the same page. He continued to count down until Day 1, September 24, 1968, which was the only blank page in his diary. On several pages in the back of the diary, he wrote the names and addresses of family and friends. On the inside back cover of the diary, there are tiny monthly calendars for the years 1967 through 1972, where he marked the days of his time in Vietnam.

The inside front cover of Louis Raynor’s diary, with his measurements and other personal information, 1967-68.

The inside back cover of Louis Raynor’s diary, in which he marked his time in Vietnam on the monthly calendars for the years 1967 through 1972.

On September 24, 1967, he wrote, “The first saddest day of my life so far. It was time for me to depart from the ones I loved so dear to go to spend 365 day tour in Viet-Nam. 12 months. My family and my love have accompanied me to the airport. When I arrived it was too late to catch a plane. I feel better. I have one more day to spend home before leaving.” He also writes about the many letters he wrote and received from home, the weather, the food, his daily duties as a soldier, the patrol missions, the number of American GIs and Viet Cong (VC) killed during battle, and the USO Bob Hope shows, as well as his many locations, such as Bearcat, Blackhorse, Red Oak, and Delta South, where there are rivers to cross but he could not swim.

The first entries in Louis Raynor’s Vietnam War diary, September 24-25, 1967.

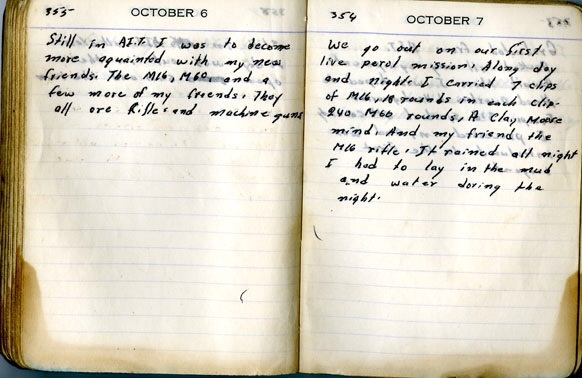

On October 7, 1967, he wrote, “We go out on our first live patrol mission. A long day and night. I carried 7 clips of M16, 18 rounds in each clip, 240 M60 rounds, a clay mortar mine and my friend, the M16 rifle. It rained all night. I had to lay in the mud and water during the night.”

His other duties were quite routine for a GI: KP (kitchen patrol or mess hall duty), filling sandbags to build bunkers, mission patrols, policing, and, particularly for him, maintenance and motor pool duties.

Louis Raynor’s diary entries for October 6 and 7, 1967.

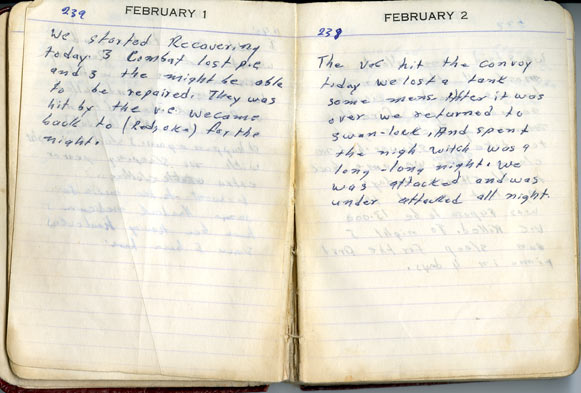

During the early firefights of the Tet Offensive, on February 2, 1968, he wrote, “The VC hit the convoy today. We lost a tank, some men. After it was over we returned to Xuan Loc (pronounced Swan-Lock) and spent the night which was a long-long night. We were attacked under attack all night.” On February 3, he continued, “We stayed on alert almost all the morning because we received some sniper fire this morning. Today I got to take a shower but no clean clothes. We came back to Blackhorse today. My last count there were supposed to be 13,000 VC killed. Tonight I can sleep for the first time in 4 days.”

Louis Raynor at work with a comrade, c. 1967-68.

Louis Raynor’s diary entries for February 1 and 2, 1968.

For his service in Vietnam and thirty-six months in the US Army, Louis Raynor was awarded the National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, Vietnam Campaign Medal, and the Army Commendation Medal. Even after he was wounded in a gas explosion while recovering a damaged armor personnel carrier (APC), he continued on active duty. He was honorably discharged on September 7, 1969, at the rank of SP/5 (E5).

Louis Raynor and a fellow soldier in Vietnam, c. 1967-68.

Louis Raynor and a fellow soldier in Vietnam, c. 1967-68.

In an oral history interview, my father shared, “There are many reasons why Vietnam veterans decided not to talk about our war experiences when we arrived home. For me, no one seemed to care about my time in Vietnam, especially people who hadn’t themselves been vets. Everyone looked at me like I had done something bad. People have mothers, fathers, brothers, and sisters, and I did not want to think about having taken that life from someone else, so I just kept quiet.”[1]

After becoming a long-distance truck driver, and when his health began to decline rapidly, he started attending a Veterans Outreach Center to help him cope with service-connected illnesses and injuries and PTSD. He said, “I found courage and strength to continue a long, lonesome, hard fight. It has made a tremendous difference to my family and me. It is easy to shut someone out when you do not understand. It was hard being criticized for doing your duty. It is a great comfort to know that someone cares about you. I have found that there are people who are willing to listen. I never realized that staying away from home was not protecting my family from those things I never talked about. Distancing myself from them only pushed them further away. I now realize that all those years I spent fighting this battle alone only made me weaker and angrier. It sometimes takes a very strong man to admit that he needs help. I feel that all veterans should have the opportunity and privilege to sit down and share their memories with one another.”

Certificate of Combat Service issued to Louis Raynor upon his honorable discharge, 1969.

Certificate of Combat Service issued to Louis Raynor upon his honorable discharge, 1969.

————————————————————

[1] For a study of the oral histories provided by veterans, see William J. Brinker, “Oral History and the Vietnam War,” OAH Magazine of History 11, no. 3, Oral History Issue (Spring 1997): 15–19. As Brinker notes, oral histories have the profound power to create atmosphere and provide vivid descriptions while containing valuable information. Unlike traditional accounts and sources, oral histories are often episodic, brief, and fragmented. But they bring the war and its impact to the human level necessary for comprehending something as chaotic as war. Properly valuing veterans’ oral history means reading and/or listening to them with a critical perspective because they often move readers and audiences beyond the general to the personal reminiscences of previously unheard and undocumented voices, which may either confirm or challenge existing interpretations of the war. In the twenty-first century, veterans’ oral history, collected and preserved by the Veterans History Project (VHP), include recorded interviews, photographs, letters, diaries and journals, military papers and documents, and even artwork as authentic representations of a veteran’s war experiences.